Issue 32: Sharing a public IP address: Network Address Traversal

Published:

Previously: A router assigns IP addresses automatically using DHCP. It reserves any registered static IP addresses for devices identified by their MAC address, and assigns the remaining private IP addresses in the pool to any devices that request one. Each IP address has a lease period, after which the device must request an IP address again.

In Issue 30, I tried to answer the question "how do all my devices manage to share the one precious IP address assigned to me by my ISP?", and in the process introduced two more acronyms: DHCP and NAT. I covered DHCP last issue, and today I’ll explain NAT. It is one of those technologies that work silently in the background, doing its own thing merrily until something bad happens.

Requests and Responses

Remember that when your phone/laptop/device first connects to the router, it doesn’t have a private IP Address yet, and it uses its MAC Address (a hardware ID key) to ask the router for one. Once it gets a private IP address, it can finally start to send and receive requests.

In Issue 8, I gave an example of the content of a response:

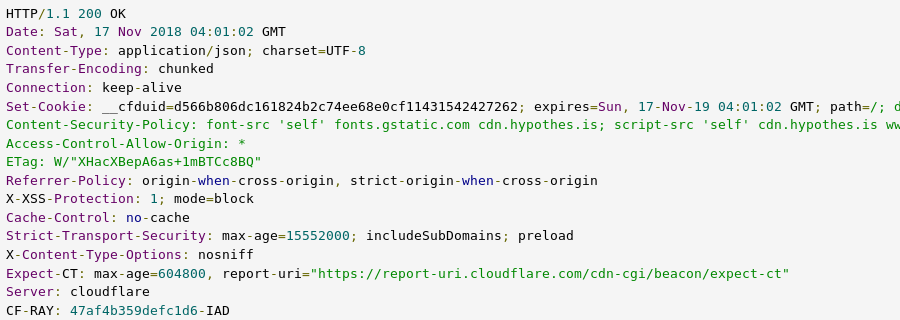

The response header from Hypothes.is

This is like the header of a letter that Hypothes.is writes to my web browser (with a company letterhead and all that), saying that it received my request (HTTP 200 OK), and the content of my request (not shown) follows after this header.

In Issue 30, I described an analogy for how packets are requested and received:

When someone sends a physical packet to you, they’ll write a home address and a name (To: ). The mailman doesn’t care that much about the name; they just send the packet to the home address. Once it reaches your home, someone in the house (the early riser, or the stay-home one) looks at the name and figures out where the packet should go. If the packet is addressed to “Peter”, it’s natural to assume that it’s meant for Peter-in-this-house and not Peter-5-blocks-down-the-street.

When I click a link or load an image, my web browser sends another request for the information. This request may include some data (e.g. if I'm sending my credit card details), or it may just consist of a header (e.g. if I’m going to a new URL). But how do I send it out?

When we write letters, we never drop them into the mailbox directly; without To or From address information, the mailman would have absolutely no idea what to do with our letter!

This is where Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP) comes in.

Transmission Control Protocol: not going into it for now

It is not the time to delve into what TCP does and how it works, but it is part of the sequence of events that lead to requests being sent. For now, just know that when my web browser sends the request, it has to go through my network card which will encode the request into an electromagnetic signal to be sent over the airwaves as a wifi signal. As it does so, a number of things happen.

One of those things is that TCP will stamp the request with some identifying information, so that when a response is received, it can be matched to the request.

Another of those things is that TCP will give the request a port number. Yes, you might have heard this term when configuring routers. We won’t need to discuss port numbers yet, so let’s put that aside.

Internet Protocol: To and From

As I type this section, it dawned on me that there is one acronym I didn’t introduce properly. All this while I’ve been using “IP address” repeatedly and never even mentioned what “IP” stood for!

Well, now we know: it stands for Internet Protocol (IP). IP is the next protocol layer in the sequence (that ensures our request gets through, and a response gets back). It is a big part of the backbone that forms the internet. At this point, our request has some identifying info and a port number, but no To or From information yet.

Where does the To: information come from? From the URL I am trying to access (or more specifically, the domain name of the URL). My web browser first sends a DNS query (Issue 28)) to resolve the domain name to an IP address, and now we have the IP address to put in the To: field. In Internet Protocol, this is the Destination address.

What about the From: information?

At this point, my network card only knows a few IP addresses:

- Gateway: this is the IP address of the router, where all requests are sent

- DNS server: this is the IP address where all DNS queries are sent

- Private IP address: This is the private IP address the router gave to my device when it first connected to the wifi

The only IP address there that is viable is the private IP address. So that is the IP address to put in the From: field. In Internet Protocol. this is the Source address.

Sending and receiving

Now our letter is packaged in a TCP/IP envelope, with a port number, source address, and destination address. It is ready to go out from the network card! It is broadcast!

Request #4676

Source IP: 192.168.1.10

Source Port: 8976

Destination IP: 172.217.26.78

Destination Port: 80

My smart TV, Playstation, iPad, and other wifi-connected devices around the house are blind as to what it contains. They all receive this request, decode the address information, realise it is not for them (the Destination address is not their private IP), and promptly discard the request.

Only the router receives this request (because it is The Gateway Through Which All Things Pass), and has to figure out what to do with it. It sees that the Destination address is not in its forwarding tables, and knows it must send this packet to another gateway (i.e. your ISP). But that can’t happen yet: the Source address is a private IP address! Those can never go out to the ISP gateway, because the ISP gateway would get confused. It would think “private IP addresses are reserved for internal use and can only come from devices within my own network, so this packet must have come from another ISP computer and not my customers”.

So your router does a clever thing: it rewrites your request.

Network Address Traversal

The router replaces the Source address with its public IP address, the one issued by the ISP. At the same time, it also replaces the port number (e.g. 80 for web traffic) with another random one (e.g. 45784, some large number between 1024 and 65535).

Request #4676

Source IP: *27.104.229.65*

Source Port: *45784*

Destination IP: 172.217.26.78

Destination Port: 80

The server responds:

Request #4676

Source IP: 172.217.26.78

Source Port: 54674 (random)

Destination IP: 27.104.229.65

Destination Port: 45784

The router sees the destination port, 45784, and realises that the outgoing packet with the same port number originated from me. So it rewrites this response to send it back to me:

Request #4676

Source IP: 172.217.26.78

Source Port: 54674

Destination IP: *192.168.1.10*

Destination Port: *8976*

And that’s how it’s done.

Issue summary: When a request from a device on the network is to be forwarded to the gateway, it has to traverse different networks. The router helps it by rewriting the source IP and port number, keeping track of the originating IP and port. When a response is received, it rewrites the destination IP and port so that the response will reach the originating device.

This issue is much, much lengthier than expected; I totally underestimated the prior-knowledge-bridging content that’s required. You notice that the NAT portion of this mailer is pretty short, but there’s a lengthy backstory to pull together disparate pieces of information from past issues.

You intuitively know that you need a router to access the internet, but might not know why. I hope this post illustrates sufficiently one of the key functions of a router :) the magic of NAT is what allows multiple devices to share one public IP address. Keep in mind that when you’re on public wifi, you may be sharing this digital infrastructure with hundreds if not thousands of other users! The hardware needed is immense; certainly far more expansive than the impression given by a home router.

As the picture gets clearer and more detailed it’s also getting more complex. My personal philosophy is “there are no dumb questions, only dumb answers”. I bet there’re tons of things I overlooked. If there’re any lingering questions, please drop me an email and I’ll try not to send a dumb answer :)

What I’ll be covering next

Next issue: All about port numbers

This next issue is fun! As you are receiving packets for your web browser, skype call, network file transfers, DNS queries, etc, how does your computer get the right packets to the right software services?

Sometime in the future: What is:

- booting up? [Issue 15]

- a cookie? [Issue 8]

- a cache? [Issue 8]

- XSS? [Issue 8]

- a CDN? [Issue 8]

- Unicode? And what does it have to do with emoji? [Issue 8]

- those '\r\n's in the HTTP request packet [Issue 12,17]?

- a good reason developers write code and give it away for free online? [Issue 21]

- ASCII? [Issue 23]

- compiling code into an application [Issue 26]?